He Lost $500,000 Betting. Now Helping Others Will Never Stop.

Virginia betting tipster Sean Fournia texts 150 of his closest friends almost every day.

“We are miracles making a difference in gambling recovery today!” he said. “No bed, no spin, no scratches, no whammies, no losses.”

Best Reads in The Wall Street Journal

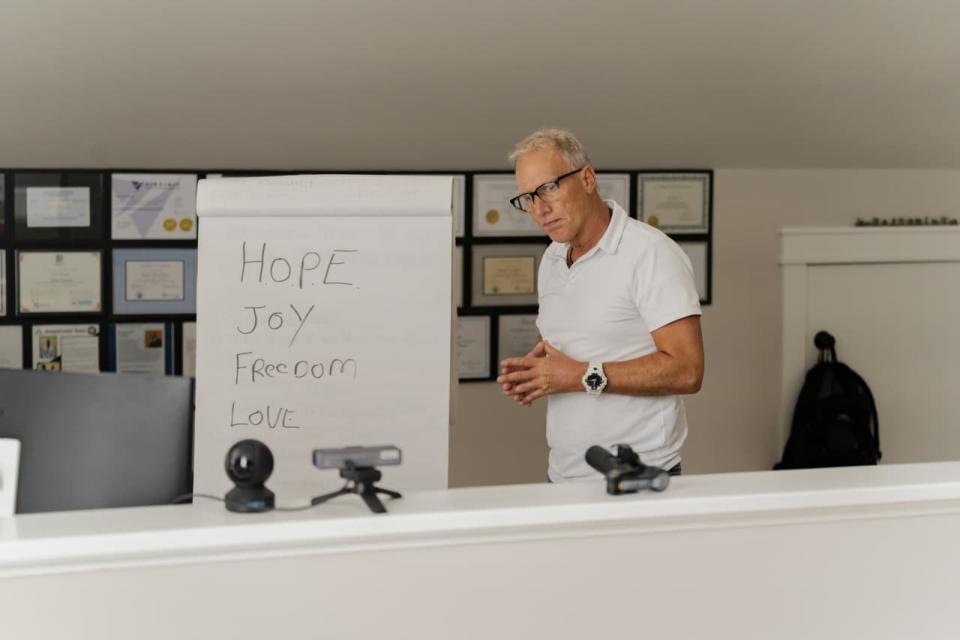

Fournia, 53, stopped gambling three years ago after decades of financial hardship and personal pain. Now, he’s on the front lines of fighting the dangerous side of America’s burgeoning gambling industry: addiction.

He advises more than a hundred people struggling with gambling habits in Virginia, where gambling is growing rapidly. Internet sports betting, casino resorts and gambling halls with similar slot machines have all been legalized in the Commonwealth in the past six years.

Virginia’s expansion of legalized gambling in recent years has been one of the fastest of any state, part of a national explosion in online gambling and betting. Following the growth is an increasing number of people seeking help for gambling addiction, a battle that does not receive dedicated government funding, unlike substance abuse.

Virginia allocated 2.5% of its sports betting tax revenue to the problem gambling fund and 0.8% from casinos.

“Betting came too quickly without really looking at how we wanted to set it up and set it up,” Sen said. Bryce Reeves, who has been a vocal opponent of efforts to legalize gambling and is helping to lead bipartisan efforts to better regulate it.

Sports betting revenue in Virginia has doubled since the start of sports betting in January 2021 to $560 million last year, according to consulting firm Eilers & Krejcik Gaming.

A state coalition that includes the Virginia Council on Problem Gambling, Virginia Commonwealth University and the state’s behavioral health agency has trained and commissioned five recovering addicts, including Fournia, as experts in peer recovery support.

Those counselors guide people who are waiting for gambling to receive mental health treatment and recovery, helping people who are legally in the program for about a year. More than 100 mental health professionals have been trained to treat gambling disorders through this program.

Calls to Virginia’s problem gambling helpline increased to 10,608 in 2023 from 989 in 2019. Those numbers include calls unrelated to problem gambling. The number of callers who went on to diagnose gambling problems increased to 898 from 311 during that period.

‘I must be dead long ago’

Fournia, who worked as a network engineer in the 2000s, estimates he bet about $500,000. Now, he sees an increasing number of people struggling to find their way to quit.

His addiction is based on Virginia’s gambling habit. The commonwealth had just started a lottery when he was 18, and he said his childhood thrill-seeking nature, including outdoor sports, drew him to an unexpected opportunity. to win a lot of money.

He said the scratch-off lottery tickets quickly became a mess, and his floor was covered in silver dust from the tickets. Years later, a racetrack opened outside of Richmond, and he began betting on horses. He became addicted to illegal books, used drugs and alcohol, and committed a series of non-violent crimes, including theft and robbery.

He had been in recovery from drug abuse for almost two years and was working in a recovery center in 2018, he started signing lottery tickets again. During the epidemic, he found himself homeless, living in a tent in the forest or in a hotel room at times, trying to support his drug and gambling habits.

He began to spend money on historical horse racing machines, a type of gambling in Virginia that was legalized in 2018. The machines offer a gaming experience but depend on the results of previous races.

He and his girlfriend were overwhelmed with donations from strangers. In 2021, Fournia no longer wanted to live. He returned to the rehabilitation center where he had previously received help and quit gambling on June 18, 2021.

Fournia said: “I must have been dead for a long time or in prison because of my gambling problem.

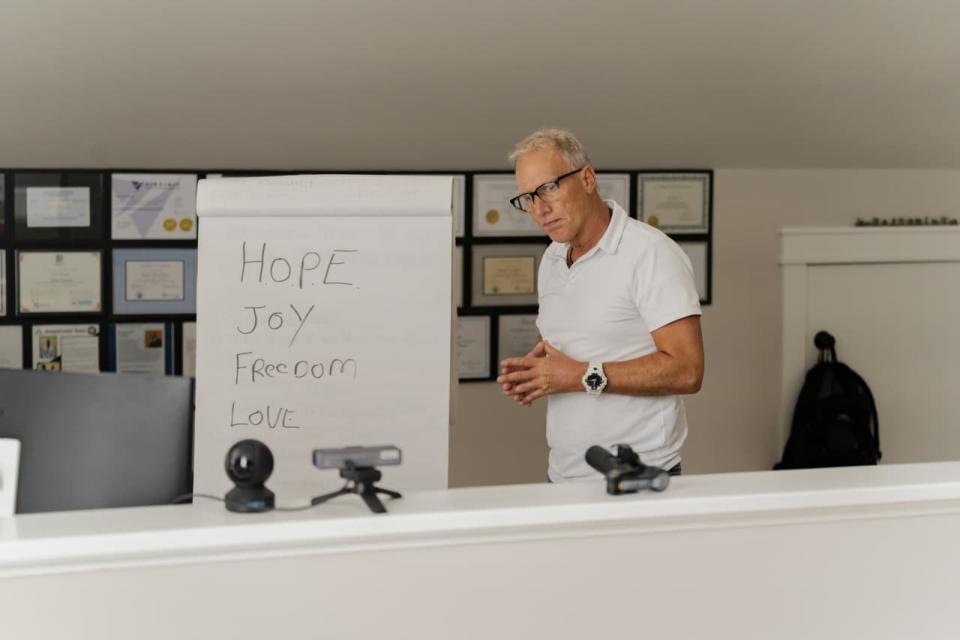

Today, Fournia counts about 120 people in his crowd, constantly communicating by phone and Zoom, in group meetings and one-on-one conversations. As the football season progresses, he is hearing from people struggling with online sports betting.

“I see despair, frustration, and financial crisis. I see marriages and children falling apart.”

Fournia says that spirituality has guided him to recovery, and he tries to help the people he advises by encouraging them to accept the jobs of their youth and telling them that obstacles are opportunities to learn.

‘The least, the last and the lost’

The program has shown early signs of success. More than half of the 677 people who spoke to the program from July 2023, when peer counselors were hired, through early September continued with ongoing treatment or peer recovery services.

Program leaders compare that to a 2022 survey in Canada that found only 7.7% of people with a gambling problem had ever received treatment.

Carolyn Hawley, president of the nonprofit Virginia Council on Problem Gambling and director of the program, said they know it’s important to help callers get treatment quickly because “it can take a long time before they can say help.”

Of the participants the program reached after a year, 95% said they had reduced or stopped gambling.

Rob Nease, 43, started gambling while in the Japanese Army, playing slot machines at a military base, and it later became an addiction that changed his life.

Nease, who joined Fournia last year and stopped gambling, helped establish a weekly meeting of Gamblers Anonymous in Richmond. “He knew what to tell me, but he also knows that you have to take it in pieces,” Nease said.

Meanwhile, state lawmakers are trying to create the Virginia Gaming Commission to regulate gambling in the Commonwealth, a process expected to take two years. Gambling is now regulated by three separate agencies.

“We have to take care of the least, the last and the lost among us in this industry,” Reeves said.

Write to Katherine Sayre at katherine.sayre@wsj.com

Best Reads in The Wall Street Journal

#Lost #Betting #Helping #Stop